Perhaps the most famous champagne in the world, Dom Pérignon was launched by Moët & Chandon as a prestige cuvée in 1936, with the 1921 being the first vintage to be released. In fact, there had been a previous, private release of a 1926 for one of Moët’s English clients, Simon Brothers & Co, but this was solely intended to be a private commission of 300 bottles for Simon Brothers’s centenary celebrations in 1935. Due to the publicity and demand that this one-off cuvée had generated, Moët offered the 1921 vintage the following year under a newly-created brand, named for the legendary cellarmaster of the abbey in Hautvillers.

The inaugural 1921 Dom Pérignon was an identical wine to Moët’s 1921 vintage champagne, due to the fact that this cuvée hadn’t even been conceived of until 1936. However, it was released in an old-fashioned replica of an 18th-century bottle, and this same distinctive shape is still used today. After the 1921, the follow-up releases of 1928, 1929 and 1934 were also Moët vintage wines, transferred to the special bottles via transversage, and the 1943 was the first Dom Pérignon to actually be fermented inside its own bottle.

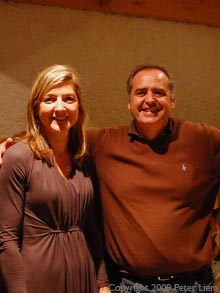

Today, Dom Pérignon is a separate brand within the LVMH portfolio, possessing a distinct identity that is kept separate from that of Moët & Chandon. Richard Geoffroy (pictured) is Dom Pérignon’s chef de cave and has been with the house since 1990: for anyone who has ever met him, it’s immediately obvious that he is highly intelligent, thoughtful and discriminating, and must surely be counted among the finest winemakers in Champagne.

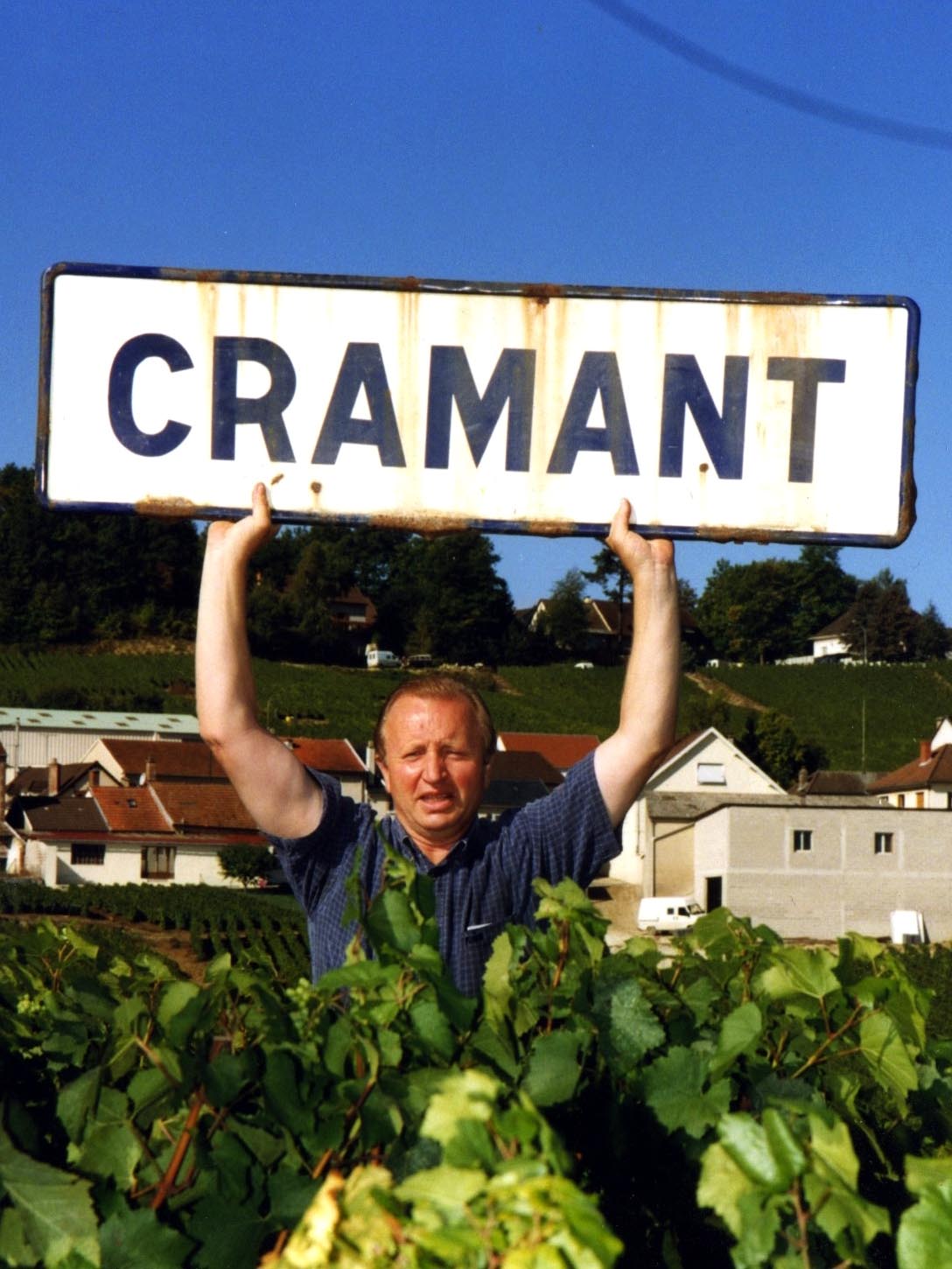

In general, Dom Pérignon is always made from the same core group of vineyards, located in nine villages: Chouilly, Cramant, Avize and Le Mesnil-sur-Oger for the chardonnay, and Aÿ, Bouzy, Mailly, Verzenay and Hautvillers for the pinot noir. Although Moët & Chandon does not disclose the exact amount of vineyard land that they own, it’s no secret that they are by far the largest landowners in Champagne, and that gives Geoffroy access to a vast and enviable palette of wines to work with. “If, in a given vintage, I need something else outside of these nine villages—a trump card to complete the blend—I can get it,” he says.

A typical Dom Pérignon blend will include slightly more chardonnay than pinot noir, although the exact blend will depend on the character of the vintage, and it’s even possible that certain vintages will contain a majority of pinot noir. “Just seeing the varietal makeup tells me a lot about the year,” says Geoffroy. “If I see 60 percent pinot noir, it means that this was not a normal vintage.”

Stylistically, Dom Pérignon is a highly individual wine. “The name Dom Pérignon is often synonymous with champagne,” notes Geoffroy, “and often, people expect it to be a classical, traditional champagne. But it is not.” He describes Dom Pérignon as possessing “a duality of youth and maturity, complexity and balance, rigor and seduction. As soon as you see one side, the other appears again.”

“To me, there are three major elements of style in Dom Pérignon,” he says. “First, we want to deliver intensity. However, there is a major confusion between intensity and power. Power is rubbish. We are not interested in power. For us, intensity needs to come from precision. It’s about harmony and completeness. Everything has to be relevant, everything in the right place.” He points out that balance and harmony are much more critical than more overt or obvious traits. “In a decathlon, you can win the whole thing without winning any of the ten events,” he says.

“Number two would be aromatics,” continues Geoffroy. “If I were speaking technically, I would say that the general character of Dom Pérignon is not oxidative, it is reductive.” The two result in different sets of aromas, he says, and he feels that reductive winemaking is more complementary to the long yeast aging that champagne undergoes, as this aging is itself reductive in nature. “Dom Pérignon in reduction causes yeast aging to amplify the characters, whereas oxidative winemaking works in a different direction than the yeast aging,” he notes. The process of autolysis can go on for decades, “far longer than you would think,” says Geoffroy, and reductive winemaking serves to bring out its full character. “Oxidative winemaking is more about aldehydes than autolysis.”

“Third,” he says, “the style of Dom Pérignon is about mouthfeel. The tactile dimension of the wine is key. Many people mention this about Dom Pérignon, the way it touches and caresses the palate. There’s always something weightless, since it’s not oxidative, and there is a seamless quality to it.”

In 1959, a rosé version of Dom Pérignon was made for the first time, but in extremely small quantities. Only 306 bottles ever left the cellars, served by the Shah of Iran in 1971 at the celebrations of the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great. The first commercially available vintage of Dom Pérignon Rosé was the 1962, released in 1970. It's a blended rosé, made with red wine from Aÿ and Bouzy—“maybe more Aÿ than Bouzy nowadays,” says Geoffroy—but it is not the same base blend that is used for the blanc. “Dom Pérignon Rosé is not the pink version of the wine,” he says. “We tend to have fewer components in the rosé blend, but the balance is the same. Chardonnay contributes a lot to the balance—it can be 60 percent pinot noir, but chardonnay has a large role to play.”

Dom Pérignon’s Oenothèque series was introduced in 2000, as a way to provide older vintages to the market in impeccable condition. While these bottles are kept in the house’s cellars and disgorged much later than the regular release, it is not Geoffroy’s goal to promote the Oenothèque as a recently-disgorged version of Dom Pérignon, and all Oenothèque vintages are aged for at least an additional year after disgorgement. “I’m not a fanatic of super-late disgorgement,” he says. “I want to give the wines enough time on the cork. Yeast aging and post-disgorgement aging bring different things to the wine, and frankly, I want both. The yeast aging is going to bring an element of complexity and of texture, and it will bring more to the finish. Post-disgorgement aging gives all of these other characters a boost. It expands them in a unique way.”

Beginning in 2014, though, the Oenothèque program has evolved into a system that Geoffroy refers to as "plenitudes": stages of evolution that exhibit certain characteristics. Once a wine has evolved beyond the first plenitude, or the first stage of its life, it enters a second, referred to as P2 on the label—"I'm looking for a peak of energy, intensity, precision," says Geoffroy. "I'm looking for it to be weightless, lifted, paradoxical." Further aging brings it to a third plenitude, or P3: "For P3, I want it to be integrated in character, sublime, comple, even more lifted, as if the peak of energy of P2 were carried even further," says Geoffroy. "You need energy to bring it back to the core—time equals energy."